What If California Governed Itself Differently? A Thought Experiment

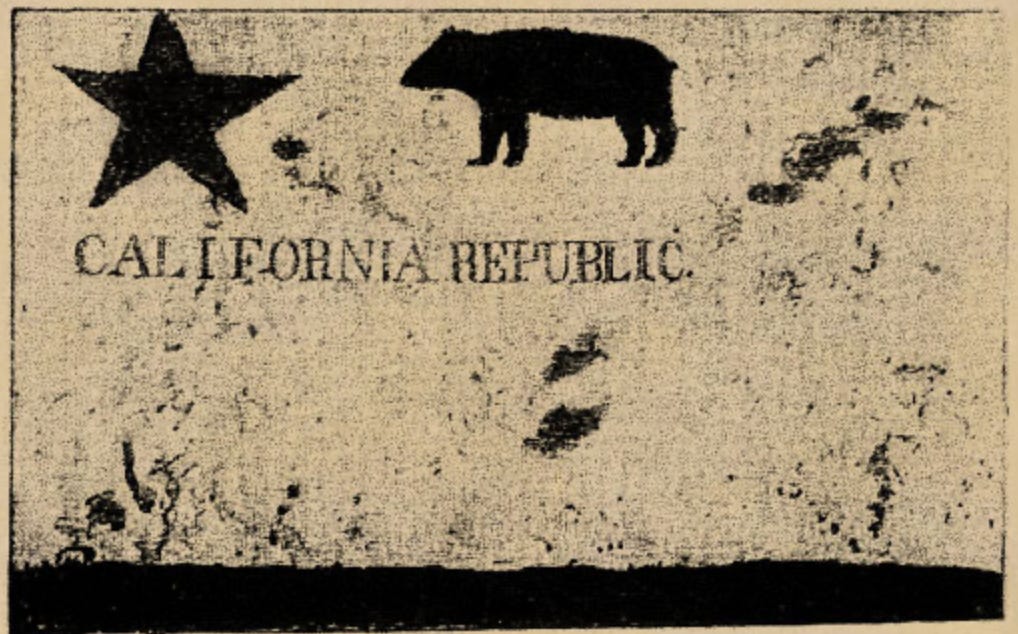

California is a state that could be a nation. Maybe it's time for something in-between.

Imagine California not just as a U.S. state, but as something slightly different. Not a breakaway republic or a tech-fueled utopia, but a semi-autonomous system within a larger one. Like Scotland in the UK. Quebec in Canada. Places that still belong, but have more freedom to govern around the edges.

What would California actually do with that space?

It already behaves like a quasi-state. The economy is larger than Germany’s—$3.7 trillion and growing. It leads in tech, media, agriculture, energy, climate policy. It has more people than Canada, more internal complexity than most countries. And its problems—skyrocketing housing, chronic homelessness, failing infrastructure, water stress, social fragmentation—scale accordingly.

The governance model it relies on—American federalism—isn’t built for this. Too much is either stuck in D.C. or fragmented at the hyper-local level. Localism without coordination. State power without responsiveness. A kind of structural mismatch.

So what if California tried something else?

It doesn’t have to invent a new model from scratch. It could borrow elements from systems that already work in large, plural, high-functioning societies. Look at Europe—not for ideology, but for operating systems.

Start with the Dutch Polder Model. In the Netherlands, where much of the country sits below sea level, cooperation isn’t a virtue—it’s survival. For centuries, farmers, workers, business owners, and governments had to work together to keep the land dry. That created a culture of consensus and shared risk. Decisions take time, but they’re built to last. Could California adopt something like that? Maybe a permanent “California Unity Council” that includes labor, agriculture, tech, and local officials—tasked not with slogans, but with working out long-range plans for housing, water, and energy. A place where interests are forced into alignment by design.

Then there’s Rhineland Democracy, the corporate co-determination system used in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. It’s not just unions and management negotiating wages—it’s workers having real seats at the table, helping make strategic decisions. It slows things down, but builds long-term trust and economic stability. What if California required worker representation on the boards of large tech or clean energy firms? Could this help redirect some of the state’s innovative energy toward building middle-class jobs again?

Swiss Federalism offers a different lesson: decentralization with accountability. Switzerland’s cantons have real control over education, transportation, health policy—and citizens vote regularly in binding referenda. That helps keep politics local without fragmenting the national fabric. In California, this could mean giving counties more autonomy over taxes and land use, but tying them into regional compacts for issues like wildfire management and water distribution. And maybe experimenting with direct digital participation—an app-based platform for key ballot measures or regional planning priorities.

Where the Models Don’t Translate

But none of these models are plug-and-play. They came out of particular histories that don’t always align with California’s.

Swiss direct democracy evolved out of centuries of cantonal autonomy and small-community governance. Dutch consensus emerged from the physical necessity of cooperating to keep the land from flooding. Rhineland-style corporate governance works partly because it’s embedded in a broader culture of social partnership—and supported by strong national safety nets.

California’s political culture is shaped by different forces: mass migration, rapid growth, speculation, booms and busts, legal battles, and deeply ingrained individualism. Coalitions tend to be transactional. Consensus isn’t tradition—it’s a new muscle, if it exists at all. Trust in institutions is low, and there’s no shared baseline of economic security.

And these European models have flaws. Swiss referendums have sometimes produced exclusionary, even xenophobic outcomes. The Polder Model can slip into backroom decision-making and stagnation. Rhineland capitalism depends on a cultural acceptance of shared responsibility that doesn’t exist in California’s high-stakes, winner-take-all business culture.

So this isn’t about mimicry. It’s about selectively adapting structures that help manage complexity and mediate conflict—reworking them to fit California’s scale and contradictions.

A Federation Within a State?

Push the thought experiment a little further. What if California functioned more like an internal federation—less like a single state, more like a coalition of metro-regions with shared infrastructure and overlapping authority? It could retain a strong state identity while letting Los Angeles, the Bay Area, the Central Valley, and the Inland Empire each operate with more autonomy over local priorities.

California could gain limited powers over issues that are now stuck at the federal level—climate migration, workforce policy, long-term investment planning—without leaving the union. Not secession. Just governance that makes more sense for a region this size.

Would that solve everything? No. But it might make space for the kinds of experiments the moment demands.

A 2026 summit could start the process: mayors, labor leaders, tech executives, local officials, community voices. Pilot projects on housing consensus models. Worker representation in the innovation economy. A participatory tool for shaping regional policy. Not silver bullets—just pragmatic steps toward a system that works at California’s true scale.

The point isn’t that California should break away. The point is that it already operates beyond the limits of the system it’s stuck in. Maybe it’s time to govern accordingly.